Aging is complex, with lots of interacting parts. A new field called “systems biology” can give us a more accurate picture of how aging works and maybe we can get closer to a cure.

We can think of a cell as a tiny submarine with thousands of little crewmen (proteins) all working together to make it work. That’s the weird ‘comic’ at the top. We have known they were in there, but we couldn’t really see them working together like this, so it was hard to make sense of it. We knew which one was the captain, and which one operated the engines, and which one operated the sensors. But how, exactly, do they all communicate? What we need is something like the “org chart” for the whole crew.

A version of this post is also available on YouTube (click here)

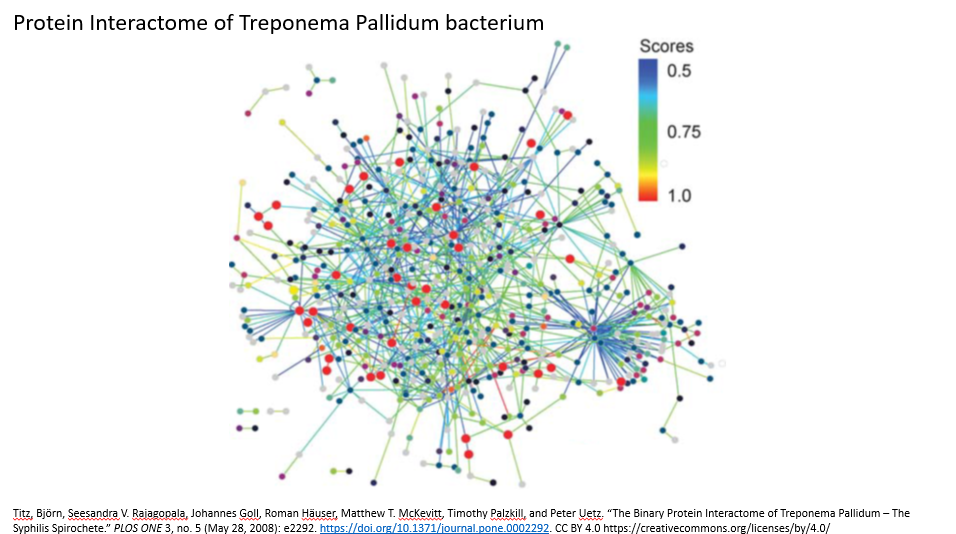

Systems biology is the use of big experimental datasets and computer models to understand biology, including the biology of aging. There’s a crazy graph that looks like a disordered mess. It shows all the different kinds of protein in a certain cell mapped out.

If the genome is the collection of the genes in a cell, this is the INTERACTOME, the collection of the interactions between proteins in the cell. This crazy web has always been there, but being able to see and map all of them at once is still fairly NEW.

When people looked through microscopes for the first time an invisible part of biology was suddenly revealed: we started to understand cells, microbes, and the results were foundational to modern life and medicine. Over the last 20 years, humans have invented new tools that rival the importance of the microscope. We are starting to see and understand things that were impossible to conceive before.

I first learned about systems biology when a researcher down the hall from me named Edward Marcotte published a high profile paper in PNAS (also covered by the New York Times!). They identified a group of molecules in yeast cells that also exist in frogs and people.

This is sort of like bone homology: a bat wing serves a very different purpose compared to our hands, but the bones all map together.

It turns out that this homology idea extends down to the protein level as well. There are proteins and systems of proteins that all interact together that are the same across very diverse species. This is freaking wild! You can find a molecular system that makes the cell wall in yeast, and then you find the same molecular system in frogs and people, even though we don’t have cell walls at all? That’s bananas, man.

If you can drug that system in yeast and see a change in the cell walls, then (if you understand the system well enough) you can predict what it will do in frogs and humans. That’s powerful stuff.

That’s systems biology: learning how things work together as a system and then applying that understanding in new contexts.

Why do we have to study things as a whole system? Let’s look back at my analogy for a cell. It’s like a bag of proteins all working together. We can plot one of those crazy web-like graphs of the interactome, but what does it mean?

It’s sort of like a schematic diagram of an electrical circuit. This is a diagram of a flashlight, but we can use symbols to represent different components. Or we could represent different kinds of components as colors. That’s what that intricate web is: it’s a diagram of what color-coded proteins connect to what other proteins.

But you can think of it as the org chart of all the little crew members in the cell. Just like a real org chart, it tells you a lot about the “who reports to whom?” That lets us understand something important about the properties of an organization. We know this about real companies.

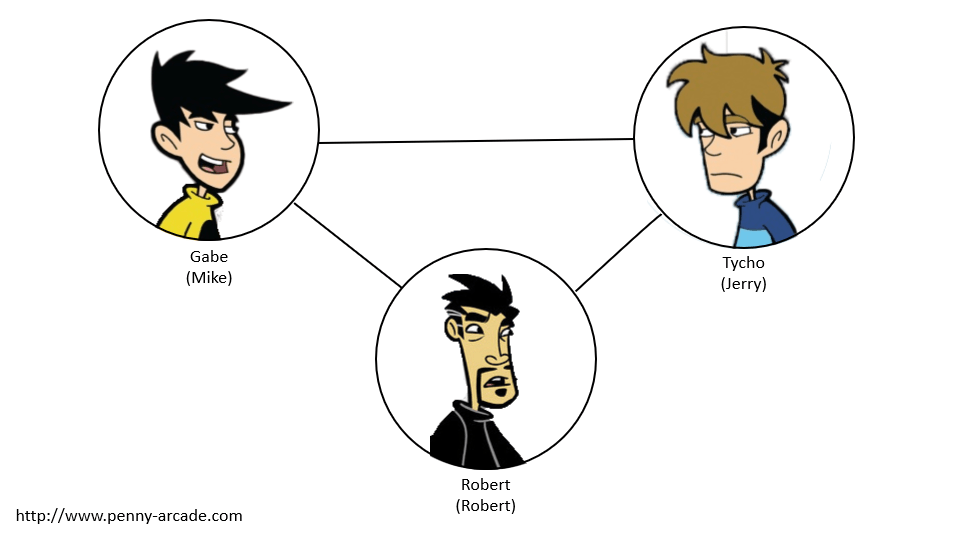

Take Penny Arcade. I’ve been reading the comic for 24 years! It started of as a collaboration between an artist, “Gabe” and a writer, “Tycho.” Between them, they produced something that neither could make on their own. They even made a comic about that when their characters broke up and Gabe made slapstick comics while Tycho wrote weird short stories about anthropomorphic punctuation marks.

The magic happens when they work together. What’s even more remarkable was what changed when they brought on Robert Khoo. He acted as their business manager. When he came along, they expanded beyond three comics per week into the Penny Arcade eXpo (PAX) and their charity that helps sick kids (Childs play) and their YouTube series like Strip Search and Acquisitions Incorporated.

They have many remarkable ventures, and those primarily came out of the interaction – the partnership – among these three people. It’s an “emergent property” or something that is more than the sum of its parts.

Emergent properties are when you connect things up together and they do new, interesting behaviors. We can see this in really simple systems too. Take a pendulum. It just swings. If you put a shorter pendulum next to it on the pivot, they just swing at different speeds. But if you connect them with a second pendulum connected to the end of the first, you get an non-periodic chaotic motion. The system launches into unpredictable behavior.

With that in mind, look at the interactome network again. What kind of remarkable properties could THAT produce?

One of those properties is homeostasis. Biology maintains a constant state while doing lots of active adjustments. It’s a steady state, but it is constantly working to maintain that state through change. It looks constant (like a river looks like it’s in the same place all the time) but it’s always changing (new water flows through the space in a similar pattern). Unlike the river, it is maintaining that pattern by continuous monitoring and tweaking – and that’s what this network is for.

Patterns like our body temperature, and our circadian rhythm of waking and sleeping – these patterns are constantly being maintained by complex webs of interactions like this.

Aging (full circle, finally) is when those patterns start to fail. It’s when patterns like homeostasis begin to break down. It’s not just things wearing out like a car with too many miles. If we are going to slow or cure aging, we need to understand aging at this level.

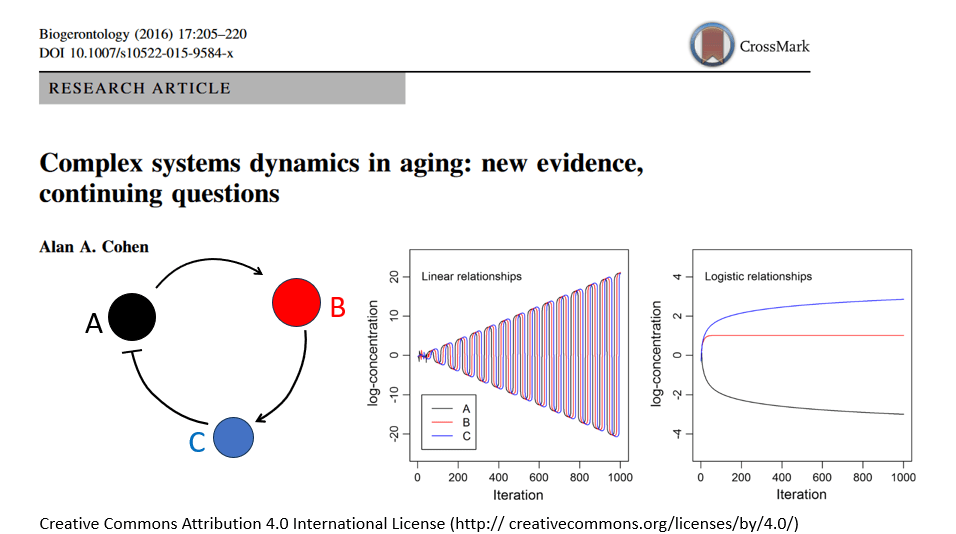

This paper by Cohen articulates that. He says that if we understand a network of interactions like this really well, not just the parts, but how they are connected, and how strongly they are connected, then we can mathematically model the whole system.

That’s what this graph is. Even if we know that these things are connected – A is connected to B is connected to C – we need to know the details. A generates more B, B generates more C, and C slows down the generation of A. But even if we know this much, we need precise measurements of how strongly those different elements affect one another. At one level of strength, you get these cycles of high and low. With another level, it looks more like homeostasis – a flatter more consistent amount of A/B/C over time.

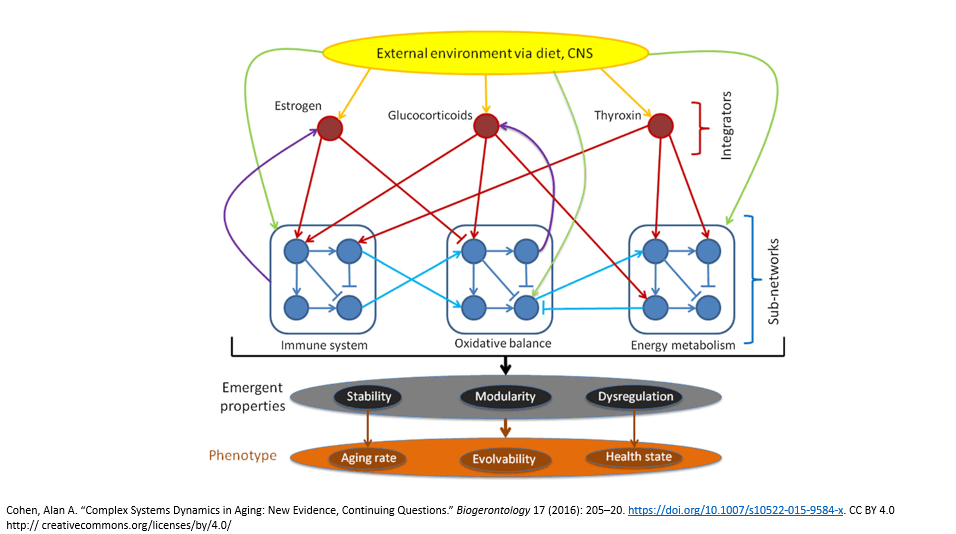

Cohen presents a cartoon version of the very complex webs of interactions that make human biology. We need to model these to understand aging. Because aging is really a change in the emergent properties of these complex systems.

Are you interested in Aging Biology? Do you have questions you would like to see answered? Drop me a link in the comments, or send me an email or voicemail! Maybe I can use your question/comment in a future video. I will leave you anonymous unless you request otherwise.

Thanks for reading!

Temporary email: comments@peterallenlab.com

Voicemail number: +1 512 487 7544

Further Reading:

Titz, Björn, Seesandra V. Rajagopala, Johannes Goll, Roman Häuser, Matthew T. McKevitt, Timothy Palzkill, and Peter Uetz. “The Binary Protein Interactome of Treponema Pallidum – The Syphilis Spirochete.” PLOS ONE 3, no. 5 (May 28, 2008): e2292. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002292

Cohen, Alan A. “Complex Systems Dynamics in Aging: New Evidence, Continuing Questions.” Biogerontology 17 (2016): 205–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-015-9584-x

McGary, Kriston L., Tae Joo Park, John O. Woods, Hye Ji Cha, John B. Wallingford, and Edward M. Marcotte. “Systematic Discovery of Nonobvious Human Disease Models through Orthologous Phenotypes.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, no. 14 (April 6, 2010): 6544–49. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0910200107

Submarine comic was created with MidJourney, composited in Photoshop and released under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) International License (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.