I managed to post three videos since my last update.

A vlog about burning Iron: https://youtu.be/46YlW8qjp_c

Burning Iron Attempt 2: pure-ish oxygen: https://youtu.be/SURy8xRsRp4

A video essay about robotics and automation: https://youtu.be/TisXw8zS5r0

The slightly expanded essay is below for your reading pleasure.

Robot essay: It’s happening now

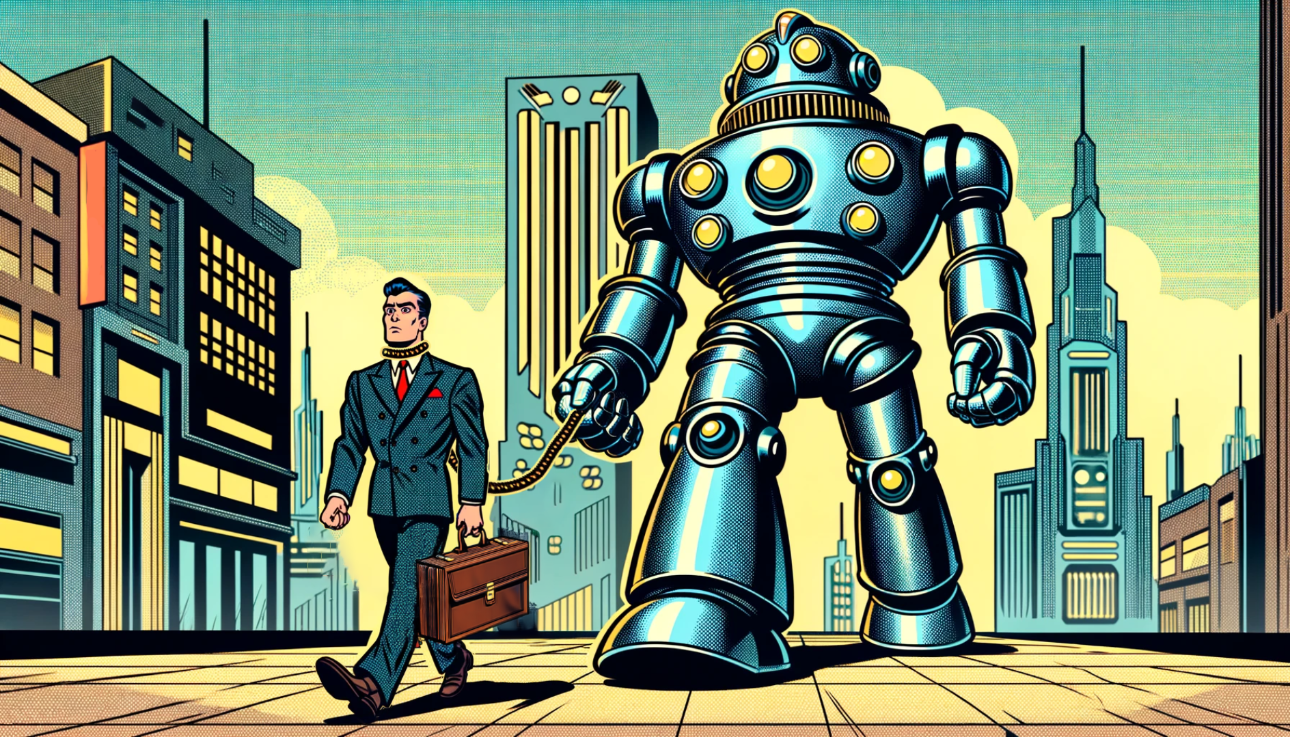

I have been writing about robots. I posted a video essay on this idea, and the text is here. I made the related comic with Firefly, Midjourney and Dall-E. I’m posting it above. The comic is the problem in a nutshell: if automation is under the control of monopolists, it’s bad for the rest of us.

Set aside the robotic tropes: robots rebelling or robots developing souls. Let’s just imagine, for the sake of a thought experiment, that robots are always loyal, and that they have no desires or agency. (To be clear, I think computation-based consciousness may be possible, but for now let’s set that aside).

Isaac Asimov explored both ideas (conscious robot people and useful but non-sentient robot automata). One of the interesting problems that Asimov grappled with was that even perfectly designed, properly functioning robots would have a strange impact on the economy.

Take this example from “The Evitable Conflict,” the last short story in the Isaac Asimov collection “I, Robot.” It emerges in the story that the god-like supercomputers (called Machines) that run the world’s economy have been making “mistakes.” In fact, the Machines have been making apparent errors in order to hide the degree of control that the Machines really have. They are actually managing us, not the other way around. That’s one strange outcome of non-hostile machines: they might quietly turn us into their pets (and we might like it).

Walk your businessman at least once per day.

Let’s look at another strange economic outcome. Let’s flip the “Evitable Conflict” scenario on its head. Imagine that the USA builds hundreds of millions of humanoid robots, each roughly as capable as an adult human: one robot per living human. What would happen?

First, is this very far-fetched? A crazy scenario? Brett Adcock doesn’t think so, and he’s CEO of a humanoid robot company that partnered with OpenAI (who make Chat GPT). He thinks that the hardware is ready. We just need the AI software. And AI software is improving at a truly amazing pace.

Here’s the quote from his interview on ARK Invest podcast: “We have an AI-first strategy to introduce [our humanoid robot] into service to do physical labor. That means putting robots into commercial opportunities to help in the warehouses and Manufacturing and Retail. And over time I have a strong belief that every human will own a humanoid, much like your car or phone today. This robot will be able to do anything you want to do physically. So, grab me a coffee, do my laundry, do this errand.”

So, at least some experts think the hardware and software will be here in just a few years’ time. It’s worth remembering that we did build hundreds of millions of automobiles during the 20th century. A humanoid robot uses less material than a car. So, we have proven our ability to roll out products on this physical scale. Maybe this is not far-fetched at all.

On the other hand, when it comes to robots, we’ve seen fakes, frauds and flim-flam artists make humanoid robot claims since at least 1939. See Elektro at the 1939 World’s Fair. So, if we are fooled into thinking that robo-servants are almost here, we would not be the first.

But let’s imagine a world where there are as many robots as there are people. The thought experiment reveals something about the economy whether we get personal robot servants or not. Setting aside dramatic robot horror stories (Will Smith’s I robot, Terminator, BlinkyTM), let’s focus on a far more likely problem. Let’s consider what functional, useful (non-terminator) robot technology does. But let’s focus on who it does it FOR and who it does it TO.

Scenario 1: Everybody gets a robot!

This robot is as capable as an adult human. You can send it to work instead of you, you can bring the robot to work with you and get all your work done in half the time, or you can work alongside your robot and double your income! Have your robot stay home and cook, clean and maintain the house while You work. Need a big lump sum? You can sell your robot!

“You get a robot! You get a robot!”

Utopian, I know. But what might this do for the economy? Let’s consider.

- Double productivity: more stuff available on the shelves

- High household income (double the workers per household)

- People can take loans against their robot’s future labor or sell their robot.

- People get more leisure

- Old people have a 24/7 caregiver and can stay in their home longer

- Young people can use the additional income and labor (or childcare) to support new families

Who wouldn’t like that? The people who lose out in this scenario are exploiters. They have enough money that they can get desperate people to do unpleasant tasks for them. They can pay young women to do degrading sex acts. They can pay those young women not to tell the press when they run for office. They can pay artists and professionals cut-rate fees or pay lawyers to figure out how to avoid paying entirely. They can pay assistants and underlings to accept abuse. In a world where everyone has a modicum of economic freedom, it will be harder to find people willing to accept those conditions.

“Robots for Everyone” is the ideal outcome. Everyone we care about gets better off. Everyone has more buying power, so the corporations and their shareholders benefit from increased sales. The general public benefits from more goods, lower prices, and more leisure time. Everybody wins.

Here’s the problem. Employers are aware of the situation. They know that their employees are now capable of doing twice the work. They can say “do twice the labor for the same price or you’re fired.” And if half the workforce quits in protest? That’s fine, because the other (more desperate) half have their robots to help. The increase in per-person productivity has been effectively captured by the employer. Sound familiar? In the late 1970s through the 1980s, women entered the workforce. The number of workers per household doubled (in many households). Did household income double? It did not. The increase in both spouses working coincides with a much slower growth in income, not faster growth.

Merely adding robots to the mix does not shift the balance of power. Even if we start with widely distributed robot ownership, it may not stay that way.

Scenario 2: Same robots, but they are owned by large corporations

At this point, the prospect of corporate-owned armies of robotic workers seems disturbingly likely. The problem with labor saving machinery has been recognized since the Luddites wrecked looms in 1811. There is an old joke (probably made up) about how Henry Ford was touring an automated factory. Someone said that it was a big improvement because robots don’t take breaks or join unions. Ford responded that robots don’t buy cars, either. If we eliminate labor from production without support for displaced workers, we create deprivation and misery. We end up hurting the economy that was supposed to benefit from the increased production capacity.

In the situation where everyone owns a robot and can direct it to help them in their economic role, people can act as consumers. In fact, in their free time, they might consume more, driving up demand and using up that spare robotic production capacity. In the scenario where corporations replace people with robots, it kills the consumer buying power. But it’s not in a corporation’s best interest to pay workers proportionate to their productivity.

It’s a classic prisoners dilemma: companies that hire humans can’t compete with automation. But if everybody automates, there are no buyers, and everybody loses.

What can we expect under the full corporate automation scenario:

- Mass layoffs and lots of underemployment

- Increased productivity: more stuff available on the shelves

- Flat or decreased household income

- Deflation, possibly a deflationary spiral

- People get less leisure; must compete for scarce positions

- Assisted Living Homes are very profitable, exploitative/automated businesses

- Young people have fewer babies because they have no security or autonomy

Does that sound familiar? This is not just a fictional scenario that might happen if we get capable humanoid robots. This is happening right now. Artificial intelligence may be a work in progress, but lots of kinds of digitization and automation are happening constantly. We see factory jobs being automated with ever more capable physical robots. We see call centers being automated with ever more capable chat bots.

What can be done

Cory Doctorow (who coined the amazing term “enshitification”) made a great point: if a bully is taking your kid’s lunch money, doubling the lunch money will not help the kid. The bully will just end up with twice as much. I am drawing from his book The Internet Con for a bunch of good ideas on next steps for democratizing technology.

What can we do about tech monopolization? What can we do to orient ourselves more toward the first scenario? I suggest that there are three kinds of power. There’s knowledge, capital, and solidarity. Knowledge is growing exponentially. But by itself, knowledge has limited potential. Merely knowing how to automate something does not produce productivity gains. We are seeing that knowledge plus capital can go much further, much faster. I believe that knowledge plus solidarity can go a long way as well.

What does that mean in practical terms? Not to get too political, but the FTC needs to keep working on fighting monopolies. They outlawed noncompetes in 2024 and that is a great step. They sued to get Amazon to stop stifling competition. The DOJ are going after anti-competitive policies at Tech companies like suing Apple for allegedly blocking other companies from accessing key features on their Iphones. They could do more to block mergers and even break up some of the big companies, but it’s a start!

We could go further. The Right to Repair movement and uptick in Union organizing give me hope. Cory Doctorow suggests that the federal government could use procurement policies to demand interoperability and competitive compatibility, or “com com.” That just means that software and hardware have to play nice with others; like how gun manufacturers can’t make their guns compatible with only their own bullet (or, they can, but the federal government won’t buy from them).

These kinds of things keep control over technology in peoples’ hands. They ensure that it’s us using technology, rather than corporations using technology ON us. Because the problem isn’t really the threat of future robots. The threat is monopolized technology – the kind we have right now – used against us.

Further Reading:

The Internet Con, by Cory Doctorow. https://craphound.com/internetcon/

The right book on the subject of undermining monopolies with the tools we have now.

Cory Doctorow’s blog post about FTC and outlawing noncompetes:

DOJ and FTC lawsuits:

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-sues-apple-monopolizing-smartphone-markets

A Practical Solution to an Urgent Need. Monthly Review. by Gregg Shotwell.

http://monthlyreview.org/2014/04/01/practical-solution-urgent-need

I want to talk more about this article, it changed my thinking about the idea of “solidarity” and unions. There are jobs that are good for the wallet and other jobs that are good for the soul. The wallet kind included an auto part job where the author machined parts to spec. The other kind was a woodworking job where he made his own tools to manufacture heirloom grade furniture. But even the first kind can be bearable if you have good relationships with coworkers.